June tugs her jeans lower on her hips, feeling giddy in the half-dark. Such a breathless night, the wind stirring the trees like a great cauldron of apples! She’d like to pull off her T-shirt, let the moonlight and foliage tattoo her breasts in shifting shadow, but she can’t quite shake loose thirty-two years of modesty. Instead she raises her arms and lifts her voice in a wordless croon. It’s a soft, high sound that dips in and out of the rustling leaves and flutters up into the night sky.

“Shut it, June.”

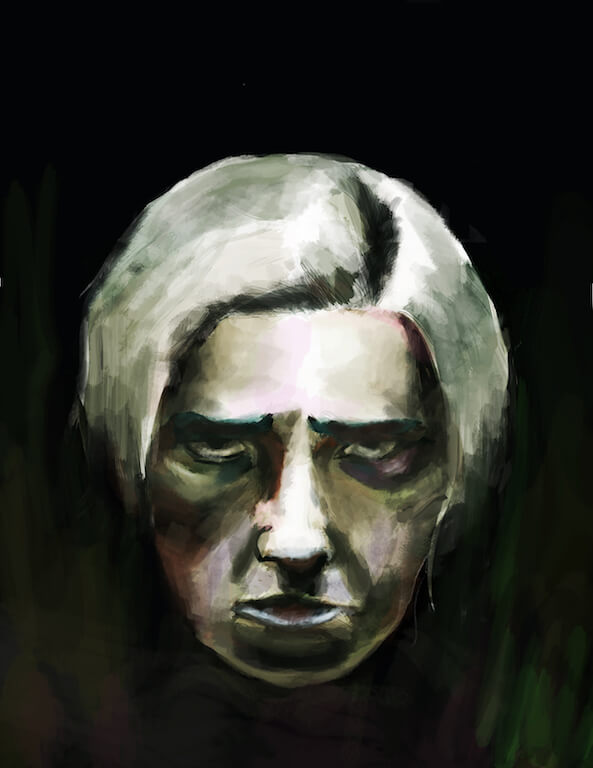

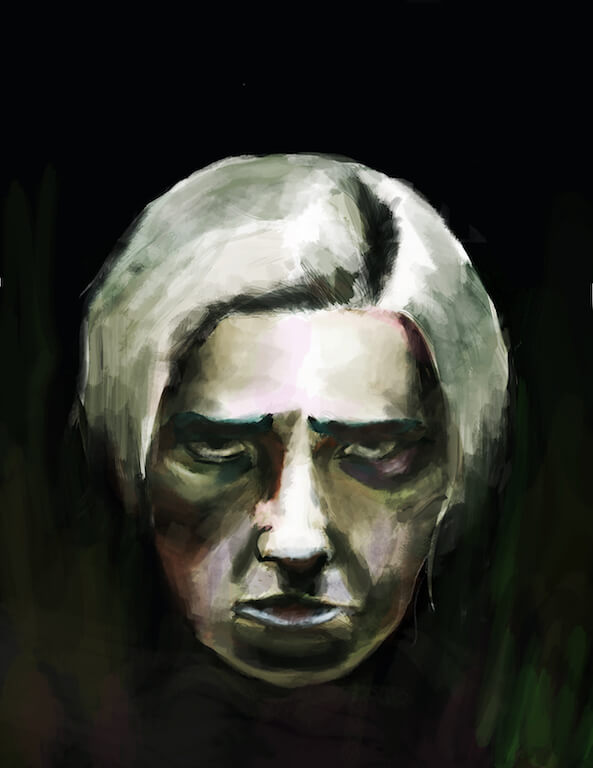

The croon pops out of existence and June looks down at Harlow. He’s scowling, propped up against the tree, reading his book with the flashlight tucked between shoulder and chin.

He really is lovely, despite the crooked nose and irritation. He has such nice hands. She longs to raise his palm to her lips, trace the line along the base of his thumb with her tongue, but last time he only frowned and wiped his hand on his jeans.

“Harlow,” she says, dropping to her knees beside him. “Harlow, let’s go for a walk. Look! Have you ever seen a full moon so bright?” And she points to where it floats, just out of reach of the drunken tips of the cider trees.

“Leave off, June.” He doesn’t even glance up. “It’s not even full.”

She looks again. He’s right, of course. It’s only almost full, and in the silence after his words it appears somehow diminished. Harlow has this effect on everything—it’s discouraging. She opens her fingers, tries to frame that roundness and keep it, but the moment has passed.

He slaps at the back of his neck. “I’m getting eaten alive. I told you a night picnic was a bad idea.”

“Mmm.” She turns away and flips open the picnic basket she lugged up from the house. It’s a good-sized basket, lined with red plaid fabric, and she bought it just for tonight. She takes out a bottle of Cabernet.

The bottle is already open, so she doesn’t get to use the fancy corkscrew that came with the basket. She pours it into a crystal wineglass. Harlow would drink out of a disposable cup—he doesn’t care—but the mouthfeel of plastic sets her teeth on edge. “Why don’t you put the book down?” she suggests.

He takes the wine from her outstretched hand without even noticing the way the liquid shivers in the glass, raises it to his lips, and turns a page.

She holds her breath. He sips.

“Are you getting hungry? Should we eat?” she asks, although she makes no move toward the food.

He nods once and continues to read. The moon waits, half-hidden behind a wisp of cloud. When his glass is empty, he hands it back without looking up.

June watches him with a troubled heart. She wraps her arms around her knees and lets the wind breathe for her until Harlow tips to one side and hits the orchard floor with a soft whump.

***

It’s a nice hole: long, narrow, and deeply slanted. Slanted things grow slower, she knows, but she wants Harlow to be able to see the sky.

She rolls him over until he’s positioned at the edge, then slides him in. He’s heavier than she thought, and it’s a struggle to get him laid out on his back with his feet in the deep end.

Once she has him settled, she begins to shove the mounds of dirt back into the hole with her bare hands. Soil pours down on his legs, covering them inch by inch. When he’s half-buried, his torso reclined against a solid bank of earth, a tremor of fear bubbles up and stills June’s hands. She straightens and wipes the cold sweat from her neck with a corner of the picnic blanket.

As she is trying to gather the courage to continue, her eyes fall on the book: Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut. Harlow only reads with his head, not his heart; he misses out on so much. It makes her throat tighten just to think of it. She picks it up and reaches in to lay the book on his chest, where she hopes he’ll be able to feel it.

As she is trying to gather the courage to continue, her eyes fall on the book: Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut. Harlow only reads with his head, not his heart; he misses out on so much. It makes her throat tighten just to think of it. She picks it up and reaches in to lay the book on his chest, where she hopes he’ll be able to feel it.

It’s tempting to leave his left hand free—then she could hold it sometimes—but in the end she decides it’s not worth the risk. She folds his fingers over the book and reaches for the shovel. Dirt rains down into the hole in a steady beat, and she forms the leftover pile into a mound to support his neck.

When she’s done, only Harlow’s head sticks out of the orchard floor, half-angled toward the sky. His eyes are still shut, but June has planned for this. She pulls from her pocket a needle and a spool of silk thread, and tacks the lids up with neat black stitches. Then she takes a small notepad from her pocket, scribbles a few words, and anchors it securely between two rocks where she hopes he’ll be able to see it:

Be back tomorrow.

***

It’s morning. June smears marmalade on toast, folds it sandwich-style, and tucks it into a paper napkin. She pours grape juice into a pop-top bottle from the recycling bin.

The hike out to the orchard is almost pleasant—the sun draws the chill from her bare shoulders, and birds call to each other through the crisscross of branches. As she crests the hill, she’s surprised how small Harlow’s head looks, dwarfed by the looming apple trees with their bounty of fruit. Her footsteps rustle on the dry grass and he swivels his eyes toward her. He’s white-faced and foamy, and the soil under the back of his neck has shifted. She pushes away a tremor of guilt.

“What the fuck, June? I can’t move! Help!” He’s hoarse and desperate. It must have been a long night.

“Are you hungry?” Shivering, she holds up the sandwich and grape juice.

“Jesus! No! I’m not hungry!” he yells. “Get me out!”

She shakes her head.

“Fuck!”

June puts the food on the grass and crouches so she can look at his face. “Don’t yell at me, Harlow.” It’s a new voice, and the sound of it gives her a little rush. “It’s not nice.”

He begins to sob. “I can’t shut my eyes. It hurts. What’s wrong with my eyes?”

“I need you to see.” She touches his cheek. It’s crusted with grime and tears, and the skin at the base of his chin looks rough and grayish.

“Jesus! See what?”

“Exactly.” June hesitates, then settles herself on the ground in front of him. She takes from her pocket a white cloth, hand-crocheted from fine linen thread. “I made this when we were first married, Harlow. Do you remember?” She waits for him to nod, but he only looks confused and angry, his cheeks flushed. “See how the stitches form tiny flowers? It’s all one continuous thread. Did you know that? It starts here, in the center, and works into itself in a spiral, moving outward until it reaches the edge.

“You can’t trace the path of that thread the way you might run your finger along a line of text, but if you study it long enough you begin to see how it must go, sense the logic. That’s what makes it beautiful.” She waves a hand, indicating the robin’s-egg sky and the whispering trees. “That’s what makes all of this beautiful.”

She holds up the cloth, and the rising sun streams through the holes, projecting a delicate pattern of apricot light onto his face. It takes her breath away.

Harlow looks straight though it. “Junie, I see it. I do. Please. Why are you doing this? Please . . .”

“But you don’t,” she says quietly. “It sits on the table by the door. You put your keys on it every night when you get home from work.”

“What are you talking about? You’re not making sense!” His voice begins to rise again.

She folds the cloth back into her pocket and stands. “I know this is hard, Harlow. But it’s the only thing I could think to do.”

“Don’t leave me here! June! Don’t . . .”

“Just think about it, okay?” She turns away and refuses to look back, humming to shield her heart from the sound of his cries.

***

June wakes to rain—a warm, gentle shower, the kind that soaks into rich soil and rises again as steam when the sun returns. She takes a long hot shower herself and soaps up twice.

In the orchard Harlow grunts out her name and shakes his head around, but he doesn’t yell.

“Good morning, Harlow.” She’s brought a fresh bottle of juice, and this time she doesn’t ask if he wants to drink. Sitting next to him, she works the pop-top between his teeth and gives the bottle a squeeze. Juice sprays into his mouth. Most of it dribbles out and soaks into the dirt, but she hopes some trickles down his throat.

“Did you think about what I said?”

He doesn’t answer, just shakes his head again.

She takes a damp washcloth out of a plastic bag and wipes his face with gentle strokes. The thin film of grime washes off easily, but to her surprise the gray patch on his chin doesn’t come away. Not only that, it appears to be spreading. It has taken over his lower lip and a protruding lump of tongue. She scrubs at it with the washcloth, causing Harlow to sputter. How strange! It appears to be some sort of problem with his skin. It’s rough as sandpaper when she runs her thumb over it, and the flesh underneath feels too firm, like a peach that’s not ripe enough to eat. She shudders.

No wonder he’s not talking.

June puts aside the washcloth and settles cross-legged on the ground in front of his head. Taking a deep breath, she says, “Harlow, I need you to listen to me now.”

Then she begins to describe to him all of the things he has failed to see over the years: how his mother’s eyes light up when he laughs; how the legs of bees are so clumsy and comical when loaded down with pollen; how the twisted trunk of the maple tree looks like the body of a woman arched back in ecstasy.

Her voice is calm, but she pours every ounce of her soul into it, as though words alone might save him.

As the sun sails higher in the sky and flushes her shoulders pink, she talks about the way the crimped leaves of Lady’s Mantle hold perfect silver beads of water after a rain, how the morning glory buds untwist at dawn, and how she herself takes up a little less space in his world every day.

She watches his eyes for just a tiny shimmer of understanding, just one sign of change.

And he does change, but not in the way she’d hoped. The gritty rash begins to creep up his nose and turn the skin around his eyes gray and expressionless. She reaches down and presses a thumb against his chin. The lower parts of his face have solidified, and they glitter with small crystalline flecks. Only his ears remain animated and pinkish. The left one wiggles, a trick she remembers from high school.

Feeling sick, she watches his eyeballs glaze over.

There’s nothing more she can do.

***

June walks out into the pre-dawn orchard, still in pajamas. It’s barely light, the trunks of the cider trees washed in gray-blue shadow and the last of the stars fleeing a navy sky. A breeze floats in and around the trees and lifts a corner of the abandoned picnic blanket.

Her chest tightens as she scans the clearing. In place of Harlow’s head a roundish rock squats in the dirt, a crooked knob poking out from one end. The coarse surface is flecked with shades of silver and gray. Around it, a fresh carpet of foliage and white buds covers the ground, spreading out from the rock in all directions, running under the trees and across the aisles.

June drops to her knees and strokes the rock. The north side is already growing a mossy pelt.

“Oh, Harlow,” she says, “It can be such a hard thing, learning to see.” And she cries for him, a little, as the world brightens.

When her tears taper off she sits quietly, remembering the shape of Harlow’s hands. She brushes her fingers over the low foliage, enjoying the way the buds tickle her palm. She breathes in the sweet air. As the light of morning streams across the orchard, a single flower wakes up and looks at her—a tiny English daisy, white with hints of pink blushing on the petal-tips and a butterscotch center. Such a cheerful little thing! She reaches out to touch it.

Next to it another bud pops open, then another. June laughs. All around her the orchard floor comes alive with tiny bursts of bloom, and soon Harlow’s earth is blanketed with a crowd of fringed faces, their golden eyes peering eagerly in all directions.

END

Kellelynne H. Riley pursues light, connection, and color in Portland, Oregon. Her work has appeared in the Bound Off podcast and in journals including The Portland Review, Poetry Quarterly, and Plasma Frequency. She can be found at www.kellelynnehriley.com.

Art by Victoria Ellison