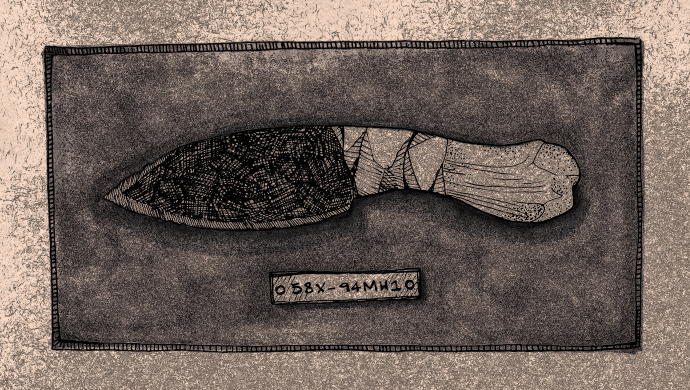

Woman’s Knife

Ruby had called in all her favors for the obsidian. A very unfeminine request, some remarked. She hadn’t collected the sharp edged slab of obsidian. Her brother’s friend, obsessed with conquering mountains, left it at her door. It all boiled down to glass. A frozen pool of translucent black that cut her fingers deep. She took this as a sign that things would work. Her pound of flesh, for knowledge that had slid away from one generation, to the next.

Ruby had called in all her favors for the obsidian. A very unfeminine request, some remarked. She hadn’t collected the sharp edged slab of obsidian. Her brother’s friend, obsessed with conquering mountains, left it at her door. It all boiled down to glass. A frozen pool of translucent black that cut her fingers deep. She took this as a sign that things would work. Her pound of flesh, for knowledge that had slid away from one generation, to the next.

But she didn’t stop for blood. Once the obsidian was lava, maybe burning up dinosaurs whole. Or was it older? Ruby never remembered geological stories. Trials and errors, cracks and splinters, blood the color of her name pulling on the surface. She finally understood the nature of the stone was liquid. Her hands moved as if manipulating water and shaped an obsidian blade.

The buck’s horn came next. This was hers, finding it on the hour-long trip from the doctor’s office to home. Her husband drove, she rode. They had just been told she was pregnant with another girl. The fourth one.

“It’s okay,” he had said, forcing a smile.

Another girl. Ruby tucked away her joy, trying to be sensitive to her husband’s dream. His want was so tangible she could see it. His son would be dark and Indian. They would create a drum and find its song. He would teach him how to hunt, fix old cars, and dance.

Their oldest girl had asked for a bow and arrow once. “Bad luck. Hunting is for men,” was her husband’s response.

Ruby did not argue, too old to play the rebel. She silently witnessed her daughter’s crushed look, then saw it change to defiance. She wouldn’t have to worry about that one. Someday the girl would find a bow and let her arrows fly.

Her husband had pulled the car over halfway between the doctor’s and the reservation so she could move around a bit. It was a long rural drive through mountains and woods. Ruby stretched her legs, wandered down a deeper path. The tree, an old oak, grew at the end of the trail. Entwined at the top of the trunk, before the first gnarled limbs split, a buck’s horn stuck out.

Ruby counted the prongs touching the tips of her fingers to each point. Five in all. She wanted it.

Tugging, it wouldn’t budge. She grabbed again, pulling, holding her breath, praying for its release. Her palms grew sweaty, eventually raw and blistered. Her grip slipped and Ruby fell. The ground was hard beneath her. Her belly tightened, a reminder of the double X life inside. She rose shakily, maybe angrily, and grabbed the stag by the horns, so to speak. She twisted hard and fell back again. This time the antler came with her.

At home, she placed her prize on her dresser. Another girl. She rubbed her belly. They hadn’t told anyone. Her mother-in-law phoned without greeting. “What is it?”

“We aren’t finding out.” The lie came easy. The phone buzzed with silence.

“I’m sure I will have a grandson.”

Ruby rubbed the horn. “Or a granddaughter.”

“I have those.” Now Ruby heard the anger in her mother-in-law’s voice.

“Yes, you do.” Ruby’s words came out like a slap.

“Is my son home?” Ruby handed the phone over and wandered off to find her girls.

She hadn’t explained the buckhorn to her husband. Now she showed it to her daughters. The three of them surrounded her, four if she counted the one inside, and five if she counted herself. Don’t count me out.

“I found it in a tree.” Ruby passed it around. “My mother told me once women carried knives. Their blades were obsidian; their handles the antlers of deer.”

The girls did not ask for a knife. The story sounded too much like a myth, not something to have in this world.

She cut and notched the horn. Really, it came down to bone. She sanded it until her nose bled from the dust and her fingers cracked from the pressure. Another girl.

The surface whispered with luster. She finished it with geometric shapes representing salmon and acorns. She searched the shores of the river for sturgeon, cast aside from men’s nets, and made their guts into glue. She tore the hide of a white deer, hunted by unknown ancestors, into string—binding the blade to the handle.

Finally finished. Strong and sharp. It was a Woman’s knife.

Dead Skin

“How long has it been since you washed your hands?” he asks. “Tell the truth.”

“About an hour ago.” I can’t really remember if that is true or not. I’ve been lost in the mall for who knows how long. Touching random objects set up in intricate displays. My hands could have picked up any number of unseen things.

My cousin dragged me here. She just got a makeover last week.

“I feel like a whole new person,” she had said.

“I don’t need a makeover,” I told her, but her clothes fit perfectly and her hair shone. Not one strand out of place.

“You should come. I’ll help you pick out some new things.”

My skin feels foreign here. It curves around me, restricting my breath, slowing my circulation.

My feet are numb, weighted down by my shoes carrying dirt on the soles. At home I spent hours putting my hair up then down, braiding it and pulling it apart. I tried on ten different outfits, but my reflection didn’t change.

About ten minutes after we came, my cousin disappeared. I wandered around trying to find her in the loose crowds of people. After three laps on every floor, I had given up. A man in a small booth, who I had ignored the first two times I walked by, offered me a free sample.

“After this, your hands will never be the same,” he says as he scoops the salt scrub on them. I know I can’t afford whatever the price is, but my hands are rough, my nails are bitten down. Soft is something they have never been. I push away the guilt of wasting his time and settle into his salesman smile with a grin of my own.

He places a wide white bowl under my hands.

“Now rub them together.”

It’s rough like wet sand.

“Can I have a little more?” I ask, thinking a thicker layer might lessen the sting.

“Absolutely.” He scoops some more. “Rub harder.”

The sting grows stronger. I wince, but he assures me it’s necessary.

“Everything old is coming off. Dirt you never knew you had is being pulled from the skin.”

I continue to scour my hands.

“Where are you from?”

“Not here,” I say. “A small Indian reservation up North.” He laughs and drops another spoonful on me.

The giant window display in the store across from his booth distracts me. There is a big blowout on make-up. All shades of polish from brown to red are on clearance. Maybe I’ll pick some up if my hands look nice enough after this.

“Have you heard of the Dead Sea?”

I bring my attention back to him. He plops another spoonful of salt into my hands. “Keep rubbing. A little harder.” I ignore the pain. Try to forget my hands altogether.

“Yes,” I say attempting to disguise any discomfort in my voice.

“What have you heard?” He places his hands on the outside of mine and pushes them together.

“I’ve heard . . .” What have I heard of the Dead Sea? I give up and shrug my shoulders. “I’ve heard there is a Dead Sea.”

“Well, the Dead Sea heals. This salt comes from there. All natural.”

He keeps talking, but the video game display right next to me grabs my notice. The game stacked so enticingly to the ceiling is the one my brother’s been talking about. First game where the main guy is native. Everyone at home wants it.

My hands begin to burn. “How much longer?” I try to break free of his grip to check them.

“Only a few minutes more. You will thank me.” He squeezes a little harder.

“You can use this on your face as well. It will remove all lines.” He glances at my cheeks. “It’s great for red blotches too. It will smooth everything out.”

My face grows hot under his scrutiny. I try to rub my cheeks with my shoulder.

He releases my hands “Don’t stop scrubbing.”

I want to, though. My hands feel raw. Stripped. I cannot see them through the salt. He gobs more on. The sweet smell floats up. Choking me. Clogging my lungs. I try to breath normally.

“You should buy a new outfit after this. Something stylish.” His arms wave in the air, drawing my attention to sale signs on a row of stores to the left.

“Everything is being discounted today.”

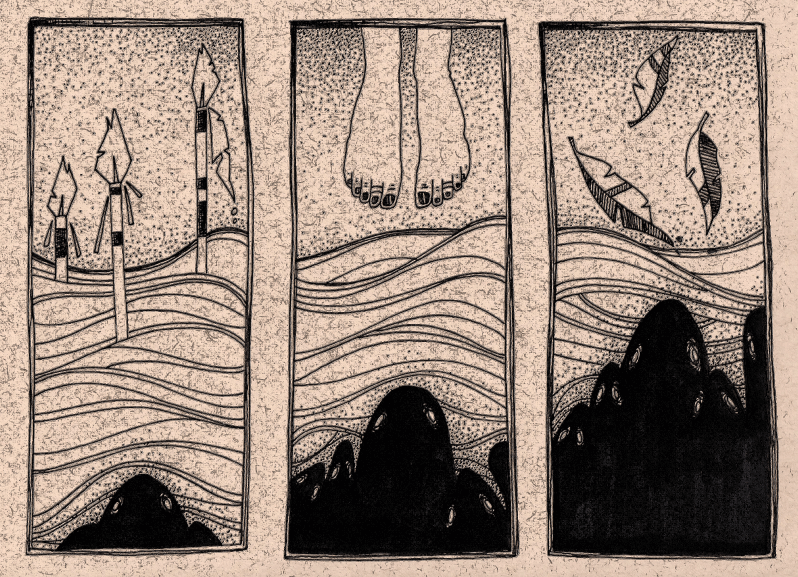

Stealing Canoes

My cousin Henry eats handfuls of ripe plums under the tree that grows from a pit my father choked on before I was born.

Henry claims to be the seventh son of a seventh son, but really is the only son of my oldest aunt.

I sneak out the door hoping my mother—asleep on the couch—won’t wake up to the sound of it shutting.

“You ready to go?” Henry spits a pit at my head and starts walking.

When my uncle drinks, he tells stories. The number of beers determines the story.

A four beer story:

“Once there were so many canoes you could go for miles down the river and never touch the water. Just hopping from one canoe to the next.”

A ten beer story:

“When I was five I was set adrift in our canoe by FBI agents while your grandfather was beaten on the shores.”

Henry and I stand on the edge of sand cliffs held together by the wild roots. Below is the river. Our grandfather’s canoe—now my uncle’s canoe—sits on the bank.

I turn to Henry. “Once there were so many fish you couldn’t see the water they swam in.”

Henry nods and races down the switchback trail that leads to the river. “Only real Indians steal canoes.”

“Yeah, but do they steal them to get beer?” I run after him.

On the river it is colder and louder. Every dip of our paddles echoes off the cliffs.

As we hit a rhythm the lights of the two-pump gas station glow on the horizon.

“They say our gas station sells more Pepsi and beer than any other store in the county.”

Henry laughs. “Probably more than the whole country.”

My chest hums with excitement. “You think anyone will buy us some beer?”

“You think anyone won’t?” Henry picks up the pace. I follow.

On the shore behind the gas station, we ground the canoe. Henry races up the hill ahead of me. I catch up before he disappears into the brightness of the lights.

“Wolfies will buy us beer.” My cousin shoves his chin at the short man sitting on the shorter cement wall.

Wolfies wears his history like Russian prison tattoos. You can tell every scar has a meaning, but you’re not sure what.

He hears his name and hops off the wall.

A five beer story:

“Coyote can show up if you say his name, and sometimes when you think it. Once I thought my woman was cheating on me with him. Sure enough, there he was, in my bed with her.”

Wolfies smiles, shows his teeth, and asks us if we’re thirsty. Henry bumps my shoulder. I pull out the money.

We earned the money picking blackberries and selling them for five dollars a gallon—except the six gallons we had to give my mother and grandmother.

“Because you damn sure aren’t going blackberry picking all day and not gonna bring some home to your family,” our uncle had said.

That night he ate the biggest slice of Mom’s blackberry cobbler.

A one beer story:

“Your mom makes the second-best blackberry cobbler. Only your great grandmother Iola’s is better. She made such good pie Betty Crocker herself stole her recipe.”

Wolfies takes our twenty dollars—wants to know where his slice of cobbler is—and walks into the gas station.

“Did you tell him what we wanted?” Henry asks.

Before I can answer, Wolfies is back with a twelve pack of cheap beer. He hands it to me. “You know your grandfather never drank a day in his life.”

I want to tell him to mind his own business, but he’s already gone.

“You think that’s true about Grandpa?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “I can’t remember him.”

“I think he kept our change.” Henry looks back.

“Let’s go back to the canoe.” I start walking. “We can drink on the way home.”

Over the rise we spot someone by our canoe.

“Is that Wolfies?” Henry asks.

“Too tall,” I say.

Hidden in the dark, I spot the old brown Dodge parked on the bank.

I try to hand the twelve pack to Henry, but he sees the old truck too and he won’t take it. I play backwards tug-of-war with him before I say fuck it and try to run. Henry, who claims there is a psychic connection between the two of us, decides to run at the same time

The beer falls. It makes no sound on the sand—on the shore—between the canoe and the lights. Everything is between the canoe and the lights, but I run anyways. Only I go nowhere. I’m held tight by my braid.

I don’t have to glance over to know my cousin is right there with me.

Braid pulled tight. Eyes watering. “How you doing, Uncle?” Henry asks.

He says it as if everything is normal. As if we were just two little boys wanting to be like him. Wanting to be like our uncle, because we can’t remember our grandfather.

A twelve beer story:

Once Coyote and Uncle wrestled for my soul behind the downtown gas station. Both of them kicked my ass and after we all drank a beer. They told stories of my grandfather until dawn, but I’ve forgotten how they go.

END

Sloan Thomas lives on an Indian reservation in Northern California. She likes to listens to stories from elders. They always seem to remind her how little she really knows. She has work forthcoming in Jersey Devil Press and Revolution John as well as, work published in Word Riot and SmokeLong Quarterly under the name R.S. Thomas.

Art by Rizza Chadwick