Premee Mohamed is a scientist and spec fic writer working out of Canada. In her spare time she paints, reads, and anxiously annotates her paperback copy of The Necronomicon in case she’s missed something.

“The bees are acting up today,” said Cole’s mother, Agnes, as she knelt to cut the last of the spring rhubarb from the kitchen garden. “Stay in the front, away from the hives.”

Cole nodded, barely listening. “Yes, Mama,” she said after a minute; but her mother wasn’t listening, either. It was the longest day, the shortest night of the year, and there was an itch to the air as if one of those tremendous summer thunderstorms was due, even though the sky was clear. Everyone wanted to crawl right out of their skin, and the household had emptied into the garden from the sheer nervous irritation of other people.

As soon as her mother lowered her sunhatted head, Cole went around to the back of the house, where the hives hummed and chanted under the shade of the oak tree. Never leave hives in the direct sun, her father always said. The bees will overheat and die. Bees need shade.

They had been the only honeymakers in the county for generations, watching with curiosity as other families with bigger and better hives, their expensive bees purchased in the mail or brought back at great expense from overseas, failed. “We are the only ones who can leave our hives so close to the woods and have nothing touch them,” her father always added; they who live in the woods have always protected them, and they will come to no harm. Cole was eleven and more or less knew that this was a story made up for her and her sister, but she always played along; she’d been hearing it her whole life and was not ready to dismiss it just yet.

The bees did seem upset about something; they were zipping around in short, sharp flights, not their usual lazy loops, and the flower garden—in full, extravagant bloom—was empty of their little bright bodies. “Hello,” Cole said. “I know you know me. What’s the matter today?” As she came closer, she saw a blob of honeycomb where it did not belong, a luxuriously glistening clump on the side of the hive instead of in the combs, strangely lobed and pointed. Cole watched as if from a distance as her hand—summer-golden, etched from raspberry canes—reached out, scraped loose a few hexagonal cells, and caught the thick honey that oozed out, bringing it to her open mouth. The bees all stopped—some even seeming to hover midair—as she swallowed, thousands of eyes turning to her with what could only be described as shock. And then they descended.

***

“Will she remember?” Agnes asked Dr. Andhera, as they stood over the hospital bed where Cole had lain in a coma for most of a month. “What happened, I mean.”

“It’s hard to say,” Dr. Andhera said. “We know so little about how memory works. And Columbine’s been very heavily sedated.”

Agnes wished she had also been offered some sedation—Valium, perhaps, like her friends had been suggesting. It would have helped with the nightmares at least. Every night she woke up gasping, fists tight in the coverlet, choking on her own screams just as she had found Cole choking on the bees that had covered her. There had been so many that she had almost suffocated. Blasted with the garden hose, the few surviving bees stumbled away, revealing the girl’s little body seizing in the grass, the skin as evenly speckled with stings as if she had been sprinkled with black pepper. The hives were silent now, most of the bees dead in their assault.

Finally released, Cole was shut up in her bedroom to finish recovering, the blinds pulled in a concession to the Vitamin D that Dr. Andhera insisted her young bones still needed. Her friends came by in solemn troupes, leaving cards and packs of scratch-and-sniff stickers on her nightside table, sometimes bringing Slushpuppies or sweets from the village shop.

“Are you terribly afraid of bees now?” her best friend, Erin, asked one day as they sat colouring near the window.

Cole looked up, where a plump bumblebee waited on the far side of the sill, forelimbs up on the glass like a furry cat sitting on its hind legs to beg for a treat. “No,” Cole said. “I thought I might be, but I’m not.” She did not mention that bees were at the window every day, at least one, often two or three, never—inasmuch as she could distinguish the honeybees in particular—the same one twice.

“Me neither,” said Erin. “I thought I might be.”

“But you’re not.”

“No.”

Cole’s mother came in and slapped a newspaper against the window to drive the bee away.

***

After two weeks in her room, Cole finally ventured into the garden again, grateful for the warm grass and the smooth stones of the pathway against her bare feet. She had thought the hives would be empty, their occupants having fatally spilled their innards onto Cole’s skin in June, but they seemed busier than ever, far more bees than they usually owned—a shimmering mob of brass-coloured bodies and blue wings.

“Hello,” she said. “It’s me again. Do you remember me?”

They roared at once, seemingly in salute, and raced off to the flower garden, now bursting with later blooms: hydrangeas and coneflowers, foxgloves and roses, the hardy geraniums that grew in the stone wall. Cole followed them, feeling them zip through her hair, sending the black strands flying like smoke, laughing at their delicate feet on her neck and wrists. She plucked and ate a pansy, her tongue diving deep into its purple heart to get at the pollen, and then a chrysanthemum, which tasted much better.

The following week, Cole’s little sister Dahlia—”Well, if we’re going to name them after flowers, I certainly don’t want anything common like Daisy or Rose,” her father had said—found Agnes in the living room, and asked her to open another bottle of jelly. “I can’t get it open on my own, and Cole’s got the other bottle in the garden,” Dahlia said.

Agnes opened the bottle, handed it to her younger daughter, and went to the back door of the house. Through the screen she saw Cole, Erin, and two girls from the village serenely eating bread and jelly next to the hives, in the dim green shadows of the trees. A fifth girl, little Savita from down the street, danced slowly in the flower garden, stepping between the stems, her eyes closed. Agnes went to the kitchen and opened the pantry, where there had been a neat row of white plastic honey tubs on the bottom shelf. Now there was only one left.

It wasn’t until she caught Cole and Dahlia outside eating tree sap that she put her foot down. “It’s nine o’clock,” she said, pushing them back inside, their bare feet silent on the path. “I simply won’t have it. Both of you are supposed to be in bed, not . . . running around like wild animals! From now on, you are to ask your father or me if you wish to be in the garden. And you’ve never shown the least interest in the woods anyway!” Her voice was trembling, but she was resolute, and pretended that she couldn’t see the shadows the bees made on the windows as they went inside.

Neither girl said anything. After the lights were out, Dahlia slipped out of bed and crossed the hall to Cole’s bedroom, stepping carefully over the creaky board. “Did you learn a new dance today?” she whispered from the doorway.

“Yes. Did you learn one?”

“I can’t remember it all,” Dahlia said. “Do you think Mama is angry at us?”

“No, Lia. I don’t think she is.” After a minute, Cole got up and put Dahlia back to bed, turning on her tulip nightlight and making sure her water glass was full. “She really isn’t,” Cole said reassuringly as she shut the door. “I promise.”

***

But as the weeks went on—both girls part of an increasing flock that seemed not so much drawn to the woods as actually incapable of staying out of them—Agnes wavered between anger and actual terror. Some nights there were other parents out there, climbing past the ‘NO TRESPASSING’ and ‘WARNING: BEES’ signs right into the back garden to drag their daughters home after the sun went down. Cole’s parents apologized, wept, raged, commiserated; some nights there were ten or twelve dancers, swiveling and bowing and turning in their white dresses as delicate as moths against the dark leaves of the woods.

“We should get one of the doctors down here,” said Ashley’s mother one night, as they stood in the doorway watching the girls disappear one by one into the woods. She tugged a packet of tissues out of her skirt pocket and dried her eyes again. “Who was with Columbine in the hospital? Dr. Andhera?”

“He did say to call any time,” said Agnes.

Dr. Andhera came out the next day, as requested, around sunset, and watched as the girls began their strange small dances, lining their shoes up neatly along the stone wall. They paused only to eat honey from the combs that had started to bulge from the loud and populous hives, decorously spitting chewed wax into their hands.

“What happens when you try to get them back inside?” Dr. Andhera said. He was very young and very handsome and was also the only doctor in the area, which gave his words the needed weight that his youth and looks had stolen from him. Agnes paused to line up a coherent answer, aware that it all sounded quite mad.

“Well, they do come in,” she began.

“Very good. They don’t argue, reason, bargain?”

“No, but then . . . sometimes I’ll go to check on them in the night and they aren’t in their beds,” Agnes said, and burst into tears.

Erin’s mother said, “Me too.”

“Same here,” said Marta and Ingrid’s father. “But they’re always back by dawn.”

“They need their sleep,” said Dr. Andhera firmly. “Especially Dahlia. What is she, seven? This is far too late. It’s not good for them. I’ll go out and have a word with Cole.”

Agnes and Erin’s mother followed him into the perfect lavender dimness of a summer dusk, to the foot of the quiescent hives. The only sound was the wind roaring through the massed oak leaves and the ranked trunks that stretched out for miles behind the house. “All right, everyone,” Dr. Andhera said, clapping his hands. “We all need to go home and go to bed, and I don’t want to hear any more of this, all right?”

Cole looked up, her face dreamy and tranced.

Dr. Andhera turned to Agnes. “Do you keep prescription medications in the house?” he said sharply. “Sedatives, tranquilizers, mood stabilizers? Anything like that? Antidepressants?”

“No!” said Agnes. “Nothing like that! Nothing stronger than Nurofen! And that’s locked up in my medicine cabinet.” She too had seen Cole’s face, the emptiness of it, but drugs had simply not occurred to her. Now that it had, she found herself more ashamed than frightened, thinking that Cole had gotten them from somewhere else, maybe even the hospital. She was at that age where girls got into trouble and lied about it, leaving behind that childhood vulnerability that is not precisely innocence but the foreknowledge that they would be apprehended at their petty unplanned crimes.

Agnes stalked forward as the other girls melted into the trees, not running exactly, almost swimming through the soft, thick air. She got Cole by the arm and said, “Right, young lady,” and then shrieked, mostly with surprise, as a bee stung her on the cheek. She had been working with bees her entire life and had been stung hundreds of times, but now she felt a bolt of real fear. They were supposed to be asleep now, but they were waking, the hum increasing, like a crowded auditorium slowly filling. Another bee stung her on the ear, its legs scrabbling there for a moment before falling away; she brushed it frantically off her shoulder and was stung on the back of her hand. Next to her, Erin’s mother and Dr. Andhera were dancing and yelping in pain. Dahlia and Cole stood hand-in-hand, untouched, watching them. As the adults fell back to the house, they too walked into the woods.

***

By the next morning, when none of them had come home, Cole’s mother started a phone chain that spread to most of the village, and they called the local police out—some fifteen miles away—to help with the search. There was no explaining it as an abduction, but in the weight of dozens of parents insisting that their daughters had all run away on the same night, it was clearly a police matter nonetheless. The police followed protocol by searching all the houses and large structures in the village first, despite numerous pleas to start in the woods, where everyone had seen the girls go. Warehouses and sheds were thoroughly examined; the church was thrown open and ransacked.

It was almost dusk again by the time they headed to the woods with the dogs, who—though amply supplied with pajamas and hats to sniff—appeared to have not picked up a trail. They cowered next to their handlers, not baying even at strands of hair caught on brambles or cloth ripped on twigs. The leaf litter on the narrow trails seemed to absorb the sounds of both paws and feet, to deaden the desperate cries of parents, the pretty names of girls falling plangently in the gloom: “Marie!” “Erin!” “Dahlia!” “Zoe!” “Columbine!” “Marta!”

Finally, Erin’s teenaged brother heard the humming, and they ran after him for over a mile through the darkening woods, sliding and wrenching ankles even with the powerful police flashlights. The night sounds of the woods sounded bafflingly close, every owl swoop and bat squeak, leaves tossing and grumbling in the updrafts as the heat of the day left them.

In a clearing not more than a few dozen yards across stood the missing girls, many in their nightclothes or light summer dresses like so many small, luminous petals under a nearly-full moon. The search party halted behind the trees and stared, not quite daring to step onto the grass, inexplicably short and cropped, studded with clover. Around the girls in a great dark vortex whirled thousands, maybe millions of bees—red-and-orange bumblebees, shy carpenters, honeybees of every size and shape. They flew so thickly that no one could see what lay on the far side of the clearing—perhaps, Agnes thought, a great statue in the shape of a woman, but it was impossible to see. But there was Cole herself, her dark hair buffeted in the wind of countless tiny wings, part of the circle of girls, hands out in front of her as if sleepwalking.

“Cole!” Agnes blurted, rushing into the clearing, feeling the small bodies bat against her face, a sting here and there, not a concerted attack. As if it were a sign of safety, everyone else ran for their child, some sobbing with relief.

Cole turned slowly, not breaking the circle. The woman who had embraced her smelled familiar, was wafting a scent she almost knew. But the call of the forest queen was greater, pulling on her with almost physical force, drowning out human words with the sound of the promised summer storm. The woman tugged on her, using one hand to guard her face. And still the storm of bees roared and swarmed.

“No,” Cole whispered. “They who live in the woods have the magic of protection, and no harm shall come to them.” Pleading in the gathering darkness, Agnes fell behind as her daughters walked across the clearing toward the half-visible giant. Cole’s last words were to her sister: “We go to begin a new hive.”

END

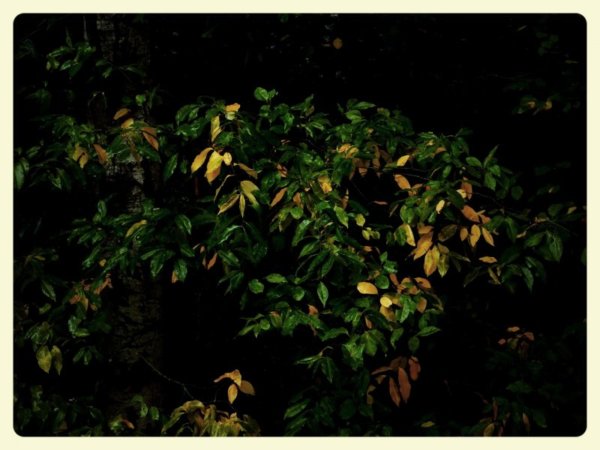

Photography by Toni Holtzman. Toni lives in Gaylord, Michigan, where she works as a hospice R.N. by day, and often night. She loves to travel, and recently returned from visits to Rome, Greece, and Israel.

All Special Issue photos are © 2016, Toni Holtzman

A Halloween Post – Premee Mohamed

[…] THE THIRD AND MOST EXCITING, AT THE MOMENT: A longer piece of mine, ‘The Honeymakers,’ (see what I mean about titles?) is in Syntax and Salt’s ‘Gods, Myths, and Monsters’ […]